At the start of July, we said farewell to Valerie, who is now based at the University of Glasgow, and hello to Jade, who joins us from Queen Mary, University of London where she recently finished her PhD. Jade tells us a bit more about joining the project and her work –

We all have stories to tell about growing older…

I’ve always thought that novels and poetry have a power to open up discussions (probably a symptom of being a serial book club go-er). But it’s something Valerie and Melanie confirmed in the work on Stage Two’s intergenerational reading groups, which combined literature with participants’ own ideas, reactions and stories prompted by the author’s ideas. From the nuanced dystopian depictions of Never Let Me Go and the mutual learning and respect found between grandmother and granddaughter in The Summer Book to the strange, intergenerational role reversals in The Last Children of Tokyo, it has been fascinating to see how novels prompt ideas, responses and solutions to reimagining the future in older age. Looking through all the data has made me very excited to delve into the ways in which literature and theatre might inform our ideas about ageing…

So, what’s ‘new’?

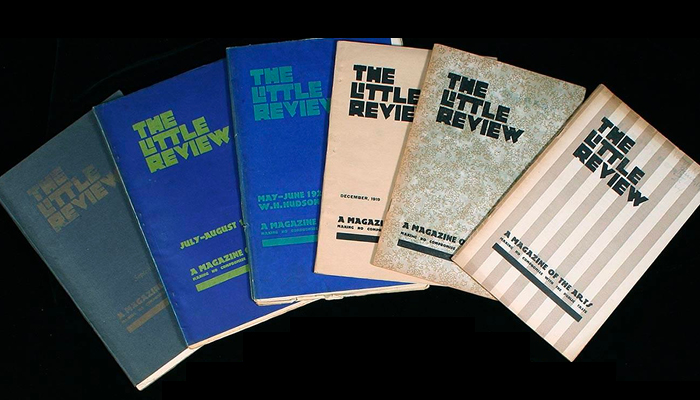

My research explores representations of ageing and late life experiences about and by older writers in the twentieth-century. Making ‘new’ work is often attributed to being ‘young’ and modernists really took this to heart. In 1910, the Futurist movement bombastically stated: ‘to youth we grant all rights and all authority’. It’s even an equation internalised by poet T. S. Eliot. On hearing of the closure of the magazine The Little Review, a venue for new work, he said it made him ‘feel that I am approaching old age’. To challenge these assumptions about the ‘new’ or avant-garde being coded as ‘young’, I focus on modernist writers like Mina Loy, Djuna Barnes and H.D., who continued making original, exciting work into the mid- and late- twentieth century. I look at how these later works were publicly received and reviewed (or, more often than not, ignored) as well as their own stories of ageing. Thinking through lived experience, as well as literary representations, this interdisciplinary research uncovers how their late works are rich, relevant and emblematic of the way women are often treated as they age.

There continues to be a general sense that making ‘new’ work equates to being young – just look at the number of emerging writer’s prizes and funds that have an age limit. Most recently the Women’s Prize has been urged to drop an age limit restricting entries to under-35’s by @noentry_arts, an account that challenges age-barred opportunities in the arts run by Joanna Walsh.

The power of metaphor

Then, older characters can also be used as metaphorical representations that retain true staying power. Broadly speaking, we might think about the metaphorical meanings of Shakespeare’s ‘Seven Ages of Man’, which describes life as a peak and a fall, or the ghostly-visage of a prematurely older Mrs. Havisham flanked in cobwebs, or years of wisdom indicated by Gandalf’s curling white beard, or the timeless yet declining quality of the grandmother, Úrsula Buendía, in One Hundred Years of Solitude and many, many more. Metaphors can be a useful literary tool but also create and draw on stereotypes for their impact, which is why it’s so exciting to be part of a project that seeks to rewrite cultural representations and challenge assumptions.

What’s next?

As we move on to analyse and share more insights from Stage 2 and Stage 3 in the following months, I’m keen to explore the links to literature and theatre, and to be part of a project that centres contemporary voices to tell important stories about how we can all age better into the future.